Evangelicals Confuse Trump for Jesus Christ

The Narcissistic Conflation of Politics and Christianity in America

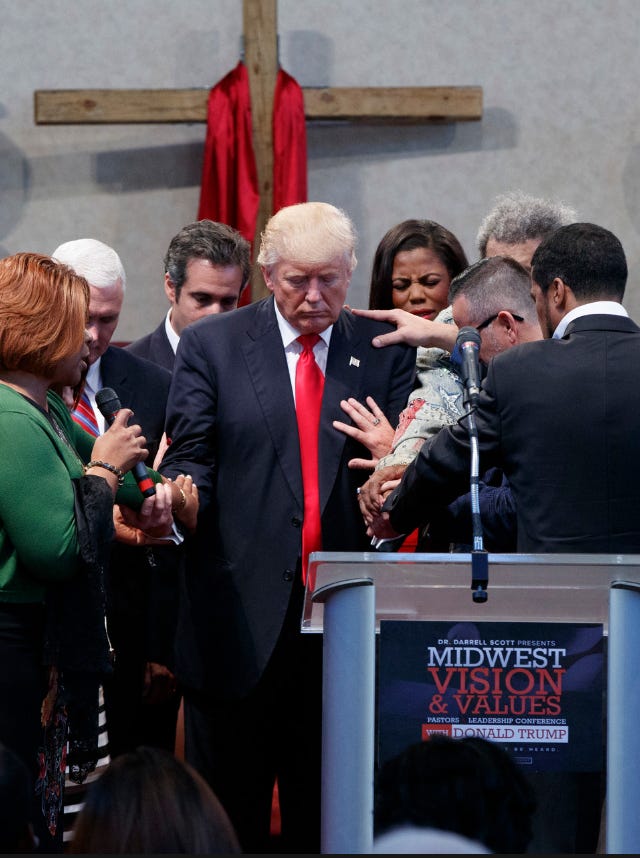

As the Iowa caucuses wrapped January 15 and Trump trounced DeSantis and Haley by a ~30-point margin it appears that America is most likely saddled with Trump as the 2024 GOP nominee for president, or as evangelicals consider him, something approximating the Second Coming of Christ, Orange Jesus.

The pundit class was bracing themselves for Trump’s brashness and gloating in his Iowa acceptance speech; instead, he was given credit for not calling Haley “Bird Brain” or DeSantis “DeSanctimonious.” Ever the gentleman, Trump failed to thank caucusgoers for turning out in subzero temperatures even after imploring them “If you’re sick as a dog, you say, ‘Darling, I gotta make it,’” Trump said at a rally on Sunday. “Even if you vote and then pass away, it’s worth it.”

Inverting that it was Jesus who died for Christians’ sins, Trump demanded the opposite of his followers, that it is they who should perish in life-threatening -30°F conditions in Iowa.

The Des Moines Register/NBC News/Mediacom Iowa poll released Saturday night revealed that the former president attracted 51% support from Iowa evangelicals. More than three-quarters of the state’s population identifies as Christian, according to the Pew Research Center, and 28 percent of the population describes themselves as evangelicals — both measures are well above the national average. What’s more, the preponderance of voters in Iowa primary elections have historically been evangelicals.

Although church attendance is in long-term decline across the country, according to the Pew Research Center the number of white Americans describing themselves as “evangelical” went up during Trump's presidency. And the group most likely to start using that label to describe themselves were the president's supporters.

Over three-fifths of evangelicals without a degree agreed that “God intended America to be a new promised land where European Christians could create a society that could be an example to the rest of the world.”

Author of the best-selling book released last month, The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism, Tim Alberta captures a conversation he had with senior pastor, Chris Winans of Cornerstone Evangelical Presbyterian Church in his hometown of Brighton, Michigan. “At its root, we’re talking about idolatry. America has become an idol to some of these people,” Winans said. “If you believe that God is in covenant with America, then you believe—and I’ve heard lots of people say this explicitly—that we’re a new Israel. You believe the sorts of promises made to Israel are applicable to this country; you view America as a covenant that needs to be protected. You have to fight for America as if salvation itself hangs in the balance. At that point, you understand yourself as an American first and most fundamentally. And that is a terrible misunderstanding of who we’re called to be.” This can happen anywhere, Winans explained, but the conditions in America are especially ripe for national idolatry. “The freedoms in our Bill of Rights, we like to call them ‘God-given.’”

“We’re clinging to something in America that is a sad parody of what Jesus has already won. We have a kingdom awaiting us, but we’re trying to appropriate a part of this world and call it a kingdom.”

“God told us, this place is not our promised land,” Winans continued. “But they’re trying to make it a promised land. Most American evangelicals are sophisticated enough to realize that, to avoid talk of a “new Israel,” to reject the idea of this country as something consecrated in the eyes of God. But many of those same people have nonetheless allowed their national identity to shape their faith identity instead of the other way around.”

“The Church is supposed to challenge us,” Winans told Alberta. “But a lot of these folks don’t want to be challenged. They definitely don’t want to be challenged where their idols are. If you tell them what they don’t want to hear, they’re gone. They’ll find another church. They’ll find a pastor who tells them what they want to hear.”

The first time I walked into the sanctuary at FloodGate, I didn’t see a cross. But I did see American flags—lots of them.

Tim Alberta, Author of The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism on FloodGate Church, which had made war with the government and increased its membership tenfold

Martin Sanders, a longtime player in the evangelical movement spent decades speaking and teaching around the world and became the director of the Doctor of Ministry program at Alliance Theological Seminary in New York. “For a lot of these people, if you’ve got a philosophy or a worldview to oppose, that became the mission of the Church,” Sanders said in The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism.

“The scary thing now,” John Torres, senior pastor of Goodwill Evangelical Presbyterian Church, interjected, “is that the enemy is inside the Church.”

“Right. And they’ll say it’s because the stakes have gotten so high,” Sanders said. “That’s what you saw on January 6. That’s why, if you’re an evangelical, you think it was okay to club the cops or break the windows. And it wasn’t Nancy Pelosi they were after; it was Mike Pence. A fellow believer. This is the biggest change I’ve observed in the last few years. The enemies aren’t those outside of the Church; it’s people in your church who don’t think exactly the way you do.”

“A longtime member of the church had asked for a meeting and broke some difficult news. ‘I’m afraid we have to leave the church after all these decades,’ the man said, ‘because you’re not interpreting the Bible in light of the Constitution.’ Torres let out a groan.”

This merger of evangelicalism with nationalism has roots going back to the inception of evangelical Jerry Falwell, Sr.’s Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia in 1971. In 1976, a student by the name of Doug Olson related that Falwell preached, “America was under assault from secular liberal elites and godless government bureaucrats, and Christians needed to start fighting back. “The nation was intended to be a Christian nation by our founding fathers,” Falwell thundered. “This idea of ‘religion and politics don’t mix’ was invented by the devil to keep Christians from running their own country!”

“When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.”

―James Waterman Wise

“We just got tired of the God-and-country stuff. It started to feel like the heart of everything we were doing, both at the school and at church,” Olson recalled. “On Sunday mornings we’d be looking at each other—my wife, my friends—just rolling our eyes, like, ‘Oh boy, Doc’s at it again.’ We had to find another church. And listen, I loved Doc. But we needed something more than just America, America, America all the time.”

Robert P. Jones, founder and president of the Public Religion Research Institute, who has written several books on conservative Christians said, “This lean into authoritarianism is about a ‘desperate times’ political ethic among conservative evangelical Christians.” While the personal values of political leaders “was all they could talk about in the early 2000s,” conservative evangelicals have now shifted “in favor of an ends-justifies-the-means ethic,” he added. “If you decide the stakes are high enough the means cease to matter, which is where I believe evangelicals have found themselves, especially if you believe God intended for us to be a Christian nation.”

The Trump conversion experience—having once been certain of his darkness, suddenly awakening to see his light—is not to be underestimated, especially when it touches people whose lives revolve around notions of transformation. And yet it reflects a phenomenon greater than Trump himself. Modern evangelicalism is defined by a certain fatalism about the nation’s character. The result is not merely a willingness to forgive what is wrong; it can be a belief, bordering on a certainty, that what is wrong is actually right.

Tim Alberta, Author of The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism

Compartmentalizing as a defense mechanism against the bruising reality that is Trump’s character, evangelicals use and exploit abortion as an “ends-justifies-the-means” Machiavellian (manipulative) cudgel, which squares with important insights from my interview with Prof. Sam Vaknin where he accounts for creeping authoritarianism world-over as an indication that humanity is falling back into the Dark Ages of the Renaissance as typified by Machiavelli’s The Prince.

Why do evangelicals accept sin in politics? “Because politics is about the ends, not the means. Since the ends are about power—the power to legislate, the power to investigate, the power to accumulate more power—the means are inherently defensible, even if they are, by any other measure, utterly indefensible. This compartmentalization of standards is toxic to the credibility of the Christian witness. Many evangelicals have come to view politics the way a suburban husband views Las Vegas—a self-contained escape, a place where the rules and expectations of his everyday life do not apply. The problem is, what happens in politics doesn’t stay in politics.” writes Tim Alberta.

If Christians are called to reflect the awesome power of a God who renews minds and transforms hearts—who dwells within us, seeking our complete devotion to Him, commanding us to lead lives of truth and love that might shine His light in a darkened world—how can there be a special exemption for politics?

Tim Alberta, Author of The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism

By conflating America with Trump and justifying this conflation through abortion, evangelicals as a demographic, if successful in their aims to re-elect Trump in 2024, will have blood on their hands in terms of America’s autocracy under Trump. As it is, Trump just last week bragged about overturning Roe v. Wade, a devastating blow to women’s reproductive rights. As for the viability of evangelicals’ holding such sway, it was Jerry Falwell Sr. who led his flock to defeat Jimmy Carter and send Ronald Reagan to the White House in 1980.

On January 14 just ahead of the Iowa caucuses, current United States Senate candidate in Arizona for the 2024 election, Kari Lake attended Soteria church in West Des Moines Iowa, and alluded to abortion by saying, “President Trump has proven himself “by achieving conservative Christians’ top policy goals while in office.”

Asked about evangelicals’ initial reluctance to embrace the real estate mogul and media personality, Lake noted how much had changed since then. “2016 seems like ancient history right now.”

Of evangelicals inverted “morality,” The New York Times reported on January 12:

America is undergoing a religious movement steeped in fanaticism but stripped of virtue. The fruit of the spirit described in Galatians in the New Testament — ‘love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control’ — is absent from MAGA Christianity, replaced by the very “works of the flesh” the same passage warned against, including “hatreds, strife, jealousy, outbursts of anger, selfish ambitions, dissensions” and “factions.”

But in the upside-down world of MAGA morality, vice is virtue and virtue is vice. Jane Coaston even coined a term, “vice signaling,” to describe how Trump’s core supporters convey their tribal allegiance. They’re often deliberately rude, transgressive or otherwise unpleasant, just to demonstrate how little they care about conventional moral norms.

Absent public virtue, a republic can fall. And a Trump win in 2024 would absolutely convince countless Americans that virtue is for suckers, and vice is the key to victory.

Here’s a guy who has his own television show. Here’s a guy who has this famous book that he wrote. Here’s a guy who has his name plastered across buildings around the world, and maybe, just maybe, all of those material successes are actually proof that God’s favor has been with him all along, that God has set this person apart for purposes that we cannot possibly perceive or imagine.

In Protestantism, you're chosen by God, and the proof that you're chosen by God is that you're successful and rich. So that's proof of this Protestant work ethic, that's the proof that God has chosen you.

A conduit to our current age of narcissism was the emergence of Protestantism:

The bridge between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment was Protestantism because Protestantism emphasized the agency of the believer.

In the original Protestantism, you did not need a church. You were in direct connection with God. You were the main agent. And if you were blessed by God, you were successful. You made money. So the Protestant work ethic is rich people are blessed by God. So this created a bridge.

This created a bridge, Protestantism, between the social locus of control and the individual locus of control. You could do both. Protestantism, therefore, was the first postmodern movement attempting to reconcile Renaissance values with Enlightenment values. —Prof. Sam Vaknin

The prosperity gospel, also known as the “health and wealth gospel,” holds that the more faith someone demonstrates, the more material comfort God provides them. Faith is most vividly demonstrated by giving money to the church, televangelists, and related Christian ventures. Because God saves us from eternal damnation through faith, the thinking goes, that same faith delivers us from poverty and sickness here on earth.

Interviewed by the New York Times, Tim Alberta said, “I think it’s that very special role that American Christianity has played in doing good in the world that creates a sort of innate sense of paranoia, that if you believe in spiritual warfare, if you believe that every day in this world there is a very real struggle between the forces of good and the forces of evil and that in order for evil to triumph, that America must fall, then you begin to associate any little change in the America that you’ve come to idealize or perhaps even idolize not just as a threat to your national identity but as a threat to your faith identity. You begin to think that if America slips, then God is himself in danger.” This kind of thinking involves paranoia and splitting (dichotomous black-and-white thinking — good vs. evil, etc.) and characterizes the narcissism endemic to evangelicalism.

In The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism, Prof. John Dickson, a celebrated theologian from Australia began, “The best explanation I have is that the American Christian has an identity crisis, that they have come to worship America in a way that creates an impediment to truly worshiping Christ and they’ve come to view them as one and the same. Therefore, any threat to America, real or perceived, is a threat to God and to God’s plan for the ages.”

“I’ve spent time with underground pastors in China and the amazing thing about them is how cheerful they are,” Dickson said. “I’ve been with pastors who have all been to prison—one of them three times. But they’re not afraid, they’re not paranoid. They are genuinely cheerful. Because they think, ‘Well, if I go to prison, there will be more people for me to preach the gospel to.’”

“It makes for an unflattering comparison,” Dickson told Alberta, with the attitude of the American Church. “Much of what drives evangelicals here is ‘fear that we’re losing our country, fear that we’re losing our power,’ Dickson said. ‘And it’s so unhealthy. We should think of ourselves as eager dinner guests at someone else’s banquet. We are happy to be there, happy to share our perspective. But we are always respectful, always humble, because this isn’t our home.’”

In the United States, Evangelicals have a personal relationship with God, one-on-one, and they can summon him, talk to him, and make demands; they expect him to micromanage their puny, meaningless lives. And if he doesn't, they're pissed off — that's religion, where humility should be the founding principle, the pillar.

“Humility doesn’t come easy to the American evangelical. The self-importance that accompanies citizenship in the world’s mightiest nation is trouble enough, never mind when it’s augmented by the certainty of exclusive membership in the afterlife. We are an immodest and excessively indulged people. We have grown so accustomed to our advantages—to our prosperity and our worldly position—that we feel entitled to them. The way to vanquish that entitlement,” Dickson said, “is by doing the lowliest thing imaginable: studying the scriptures with PhD-type rigor and kindergarten-level vulnerability.”

“There are Bible people, and there are non-Bible people. I’m just not sure how many American churches are filled with Bible people,’ Dickson said. ‘In America, there is so much focus on the illustration, on the modern application, compared to that boring, stiff British Anglicanism with its constant emphasis on the scripture itself.’ He tapped two fingers on his Bible. ‘Maybe we could use something more boring.’”

What binds right-wing pastors together, Alberta wrote, is that they are now expected to be something more than mere church leaders:

They are political handicappers, social commentators, media critics, and information gatekeepers. And they have only themselves to blame: It turns out when a pastor decides that churches should do more than just worship God, congregants decide that their pastor should do more than just preach. This might be precisely what some pastors had always hoped for, the opportunity to guide and shape every aspect of their congregants’ lives. But spiritually speaking, this is a doomed proposition. Pastors already struggle to provide all the answers written down inside their book. In a modern evangelical culture that punishes uncertainty—where weakness is wokeness, where indecision is the wrong decision—asking pastors to provide all the other answers is a recipe for institutional ruin. Because what their congregants crave, more and more, is not so much objective religious instruction but subjective religious justification, a clergy-endorsed rationale for living their lives in a manner that might otherwise feel unbecoming for a Christian. Down this path, disaster waits. The pastor who finds himself offering religious justification today might find himself inventing it tomorrow. In the darkest chapters of Church history—the Crusades and Inquisition, the slave trade and sexual abuse scandals—the common denominator has been a willingness on the part of Christian authority figures to distort scripture for what they perceive to be some greater good.

Narcissists and evangelicals are both delusional; it's beginning to look like they're one and the same. Extremists are now running civic and religious life in America. Gatekeepers who once kept crackpots away from positions of authority no longer exist.

Resources:

The synthesizing of Christianity and conservatism:

God made Trump viral ad

The cued-up video below of Prof. Sam Vaknin captures the religiosity of narcissism:

Partial transcript:

What is narcissism? What happens to the narcissistic individual at a very early phase in early childhood? The child experiences abuse and trauma.

The child says, I can't take it anymore. It hurts. I'm in pain. I'm going to invent an imaginary friend. And this imaginary friend will protect and firewall me. It will be a decoy. All the pain and the abuse will go to that imaginary friend, not to me. This imaginary friend will be everything that I'm not. I'm small. He is big. I don't know many things. He knows everything. I am powerless. He is all powerful. My mommy tells me I am bad. He is perfect, etc. He is everything I am not. Now, make a list: all powerful, all knowing. What is this? God. The child invents a private religion. He invents God. He discovers God. The false self, this imaginary friend that protects the child, is God.

The main function of God was always to protect humanity. People invented God to protect them, because they were small, powerless, ignorant, frightened, and abused by the elements and others, and they wanted an imaginary friend to protect them. They invented God, as does the child. The child invents the false self as God and then it's a private religion with one worshiper and one god. The god is the false self. The worshiper is the child. As the narcissist grows, his religion, his private religion becomes missionary. He is trying to recruit you to his religion. He is trying to force you to tell him that his false self is not false, that it's real. In other words, he's trying to convert you like the missionaries did in Africa; he's trying to convert you to a believer in his false self. He wants you to tell him, yes, you are a genius. Yes, you are handsome. Yes, you are brilliant. Yes, you are perfect. Your false self is not false. It's a true God. It's a God of life. It gives you accurate information about yourself and about the environment.

It's a survival tool and mechanism. Believe in it. Worship it. In the initial stages of narcissism, there's also human sacrifice. So already you're seeing the elements of religion. You're seeing a god-like entity. You are seeing missionary activity. These are all hallmarks of religion.

And now I'll come to the next one: human sacrifice. At the initial stage, when the child invents the private religion and his new God, he makes a human sacrifice, but it's a child. He has no access to any other person except himself. So that's the human sacrifice he's offering. He sacrifices himself: the child to this new God. And he sacrifices what we call the true self. That's why the narcissist has no true self. He has no true self because early on he sacrificed it to the Moloch, to this new God, to this new insatiable, voracious God, and he's left empty non-existence.

Narcissism is not a disease of too much existence. Narcissism is a disease of absence, and a narcissist is a void. It's an absence. It's a hall of mirrors. It's an empty corridor with howling winds. It's deep space. There's nobody there. The self that used to be there has long been sacrificed to an unforgiving god, the false self.

And now, we wrap it up on the social level, as more of us become narcissistic, via technological means, otherwise, education system, bad parenting, as more of us become narcissistic, more of us have private religions, more of us have false gods, false selves, more of us make human sacrifices, more of us try to convert each other.

Narcissism is a postmodern religion because it's distributed. It's a network religion. It's a religion with multiple gods, multiple worshippers, multiple temples, multiple shrines, multiple human sacrifices, where every god is someone else's worshiper, and every worshiper is someone else's god.

Another insightful stimulating article. Thank you. When Jerry Falwell was getting started connecting his religion to political power, many American evangelicals and the religious minded in general worried that they and their worship would be corrupted by this connection. Turns out they were correct in their concerns.

Nevertheless, though many evangelicals may "confuse" Trump with a second coming, that doesn't seem even the half of it. As I listened to Iowans who did not reference scripture but were drawn to Trump and seemed otherwise sensible and solid, my puzzlement deepened at Trump's increasing hold on his midwestern salt-of-the-earth base. The Christ comparisons and explanations did not quite hit the mark with the folks I watched, especially as their support grew with each indictment, though perhaps the prodigal son returning works.

Then yesterday morning a music algorithm out of the blue played a Woody Guthrie dust bowl song about Pretty Boy Floyd - the myth, of course, not the "reality," and it struck home. Bonnie & Clyde, The Grapes of Wrath; The Rainmaker. The other bandit heroes and heroines and bunko artists of that Depression era and most every era where hope outruns reality. The myth of the bandit savior. Take the myth of Charles A. (Pretty Boy) Floyd, an apple cheeked mid-western American.

In the song and myth, he's a desperate man on the run from unjust lawmen for a justified crime. A criminal, perhaps, but one who stood up for the neglected & forgotten, who paid off farmers' mortgages with his stolen money and by burning down banks and the mortgage papers inside; who begged a night's rest of farmers and left $100 bills under his pillow in the morning. That myth appeals even to me, if you somehow could graft it on to a billionaire NY'er, which his base has somehow done.

Watch Trump's campaign talks and don't critique them like a politician or news anchor but see them as entertaining tent shows set up in farmer's fields rife with snake oil salesmen and revivalists like Billy Sunday (a top baseball player like Falwell) or Aimee Semple McPherson or Jim and Tammy Faye Baker. Also the Rainmakers of those desperate drought ridden days. Anyway, that's three myths ever popular in the midwest/rural lore just waiting for hard times and the right person to attach them to.

Here's a Youtube link to the Woody Guthrie song which is more compelling than my above hypothesis. I understand most would not trust clicking on it, but the song is easily found by googling Guthrie & Pretty Boy Floyd

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H53yLW7aTSE

Thanks again for stirring the pot and setting the table.